March 4th, 2024

Behind The Blueprint is a series from the Local News Network at the University of Maryland’s Philip Merrill College of Journalism.

BY KIERSTEN HACKER, CHRISTINA WALKER AND ELA JALIL, March 4th, 2024

ANNAPOLIS, Md. — Maryland’s Democratic-led legislature passed the Blueprint for Maryland’s Future in 2021, vowing to pour billions of dollars into the state’s public schools to offer universal pre-K, improve teaching and make sure students are ready for college or careers.

But the General Assembly didn’t outline a long-term plan to fund the ambitious 10-year education reform effort — which increasingly looks like a blueprint for red ink.

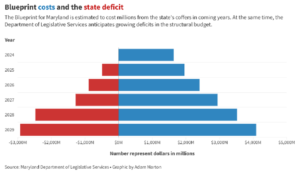

Diving deep into the reform plan in reporting “Behind the Blueprint” — a multi-part look at the state effort — the Local News Network at the University of Maryland found that the Blueprint is already devouring hundreds of millions annually from the state’s fund balance, which is on target to be fully drained in 2027.

And according to a state Department of Legislative Services fiscal briefing released in January, the state will start running a structural deficit in fiscal year 2025 that will multiply nearly sixfold by fiscal year 2029, when it will hit $2.93 billion. Not coincidentally, that fiscal briefing estimates implementing the Blueprint will cost more than $4 billion in 2029.

The General Assembly’s plan for dealing with the cost crunch? There isn’t one — at least not yet. Neither Gov. Wes Moore in his State of the State address nor any of the Democratic state legislators interviewed for this story have offered any potential solutions for the coming Blueprint cash crunch.

“Several years from now we’re going to have to have a much more direct conversation about the long-term costs,” said state Senate President Bill Ferguson, a Democrat from Baltimore City. “But we’re not there yet.”

Republicans, meanwhile, see the Blueprint as a budget-breaker.

“We cannot pay these billions and billions of dollars in extra monies — not just state but local as well,” said House Minority Leader Jason Buckel, R-Allegany. “We can’t pay for them unless you’re going to talk about new taxes — and significant taxes.”

The Blueprint’s background

Ironically, the Blueprint was born out of a commission supported by a Republican governor — who later backed away from the plan because of cost concerns.

In 2016, then-Gov. Larry Hogan and the General Assembly created the Commission on Innovation and Excellence in Education to assess the public education system in Maryland and determine whether current funding schemes were conducive to student success.

Headed by William Kirwan, the former chancellor of the University System of Maryland, the commission came to the conclusion that an overhaul was needed.

“One of the ‘aha’ moments of the commission was really to face the fact that in Maryland, on what we call the Nation’s Report Card, Maryland’s score was about in the middle … and moving in the wrong direction,” said Rachel Hise, executive director of the Blueprint’s Accountability and Implementation Board, a state entity that’s making sure school districts adhere to the plan.

But Hogan had an “aha” moment of his own after Democrats crafted the Kirwan Commission’s report into comprehensive legislation. In 2019, Hogan criticized the pending reform proposal, telling a group of county officials it would mean “billions and billions more in mandated spending increases for county and state taxpayers,” according to The Frederick News-Post.

Hogan vetoed the bill creating the Blueprint in May 2020, saying he did not want to raise taxes amid the COVID-19 pandemic to fund the education plan. The General Assembly overrode his veto in 2021.

And the following year, voters elected a strong backer of the Blueprint — Democrat Wes Moore — to succeed Hogan, who is now running for a U.S. Senate seat.

On the first day of the current legislative session that began in January, Moore said he believes in the reform plan and he will work with the General Assembly to ensure the Blueprint is implemented properly and sustainably.

“I believe in the premise and the promise of the Blueprint. I think we need a world-class education system in the state of Maryland,” Moore said. “I think that’s going to be a prerequisite for us to be able to accomplish the economic goal that we’re hoping for.”

Lofty goals

In the state’s 24 public school districts, the Blueprint and its lofty goals are already beginning to take shape.

Each school district has already drawn up a preliminary plan for how it will meet targets for offering pre-K, increasing teacher salaries and improving student performance. The Accountability and Implementation Board has approved all those plans after first asking for revisions.

The Blueprint is meant to revamp the state’s education system by presenting the same opportunities for all students. With a law like the Blueprint, one size has to fit all to achieve its goals of maximizing reading and math skills, as well as increasing pathways into college, said Sen. Jim Rosapepe, D-Prince George’s and Anne Arundel.

“So we want that for every kid across the state. We don’t want variation of those goals,” Rosapepe said. “Now, the details of how stuff is paid for — I mean, I think that’s a conversation that will be ongoing.”

Cheryl Bost, president of the Maryland State Education Association, said the teachers union is fully behind the Blueprint.

“We have a shared understanding that our goal is for students to succeed academically and become valuable citizens in our state and in our country,” Bost said. “In order to do that, we have to make an investment in public education. I think for the most part, the Blueprint identifies where that money has to go.”

What it doesn’t do, however, is identify where the money will come from. Bost, whose union represents 74,000 educators in the state, acknowledged the concerns about the Blueprint’s cost. But she indicated the increased spending on education is both needed and long overdue.

“We constitutionally have to provide a public education for all students, so the investment is needed,” Bost said. “And when some people balk at, ‘Oh, it’s all this money’ — well, we’ve been starving public education for many years.”

The budget dilemma

The Blueprint remains fully funded in Moore’s latest fiscal year 2025 budget proposal, leaving many lawmakers to turn their attention to other legislative issues this year. Ferguson, the Senate president, said in terms of current Blueprint funding, “we’re more than fine.”

But that’s not so in the long term. The cost of implementing the Blueprint is projected to grow from $1.6 billion in fiscal year 2024 to $4.1 billion five years later, according to the Department of Legislative Services. Meantime, the state’s structural budget gap is set to balloon every year through 2029 — when Legislative Services expects it to be $2.9 billion and the Moore administration says it will be about $3.5 billion.

Closing that budget gap will be immensely difficult, said Christopher Summers, president and CEO of the conservative Maryland Policy Institute, who also said the Blueprint should be paused.

“Raising taxes (is) not going to solve this problem, and I think the governor knows that,” said Summers, who has been critical of the Blueprint for years.

The Blueprint calls on school districts to increase education funding too, thereby prompting Summers to say that county budgets face the biggest fiscal threat.

But in Annapolis, lawmakers from both parties acknowledged that the General Assembly will have to make some tough decisions in the years to come as the Blueprint’s bills come due.

“I think we know the reality that we’re facing. And I think there’s gonna be a lot of discussion about that,” said State Sen. Guy J. Guzzone, a Democrat from Howard County. “I just don’t know that there’s an immediate answer.”

One obvious solution would be raising taxes to cover the state’s coming shortfalls. But Senate Minority Leader Stephen Hershey, a Republican from the Eastern Shore, said a solution lies in cutting back the demands of the Blueprint rather than paying for the sweeping overhaul as it stands.

“Republicans have stated very often that we need to move to a ‘Blueprint lite’ or you know, some type of education reform that takes some of the important components of the Blueprint, but at the same time is affordable and allows counties to make decisions on which parts of the Blueprint are more meaningful in each of their public school systems,” Hershey said.

Democrats, however, back the current Blueprint, despite its cost. Del. Ben Barnes, a Democrat who chairs the Appropriations Committee, said legislators should start talking about a long-term payment plan for the Blueprint now. The shared values between the legislature and the governor will bring them together, Barnes said, to solve the Blueprint budget dilemma.

“This legislature, the governor, we share values, and those shared values include all the priorities of the Blueprint,” Barnes said. “Getting to children who live in communities of poverty, taking care of special needs students, I mean, these are what we all ran on. And so I feel confident we’ll find the revenue we need to support that program.”

Several state officials have said they are looking to the Accountability and Implementation Board to issue recommendations regarding the Blueprint’s budget challenges. The board has made policy proposals included in bills that, if passed this legislative session, would make adjustments to the law without changing the finances.

In addition, the board is set to release additional recommendations this legislative session.

“What the AIB has tried to sort of suggest is like, let’s try to implement it the way it’s intended. And if it doesn’t work, if it’s just no longer the right thing to do, then we need to change it,” said Hise, the board’s executive director. “But for many things, we haven’t gotten to that point yet.”